In Defense of Precision Dijkstra Wittgenstein and the Void of Stupidity

In Defense of Precision: Dijkstra, Wittgenstein, and the Void of Stupidity

Introduction In 1978, Edsger W. Dijkstra penned a fiery and often overlooked note titled On the foolishness of ‘natural language programming’. At its core, it’s a technical argument: human languages are too ambiguous to reliably instruct machines. But between the lines, it reads like a cultural critique. Dijkstra wasn’t just concerned with programming — he was worried about thought itself.

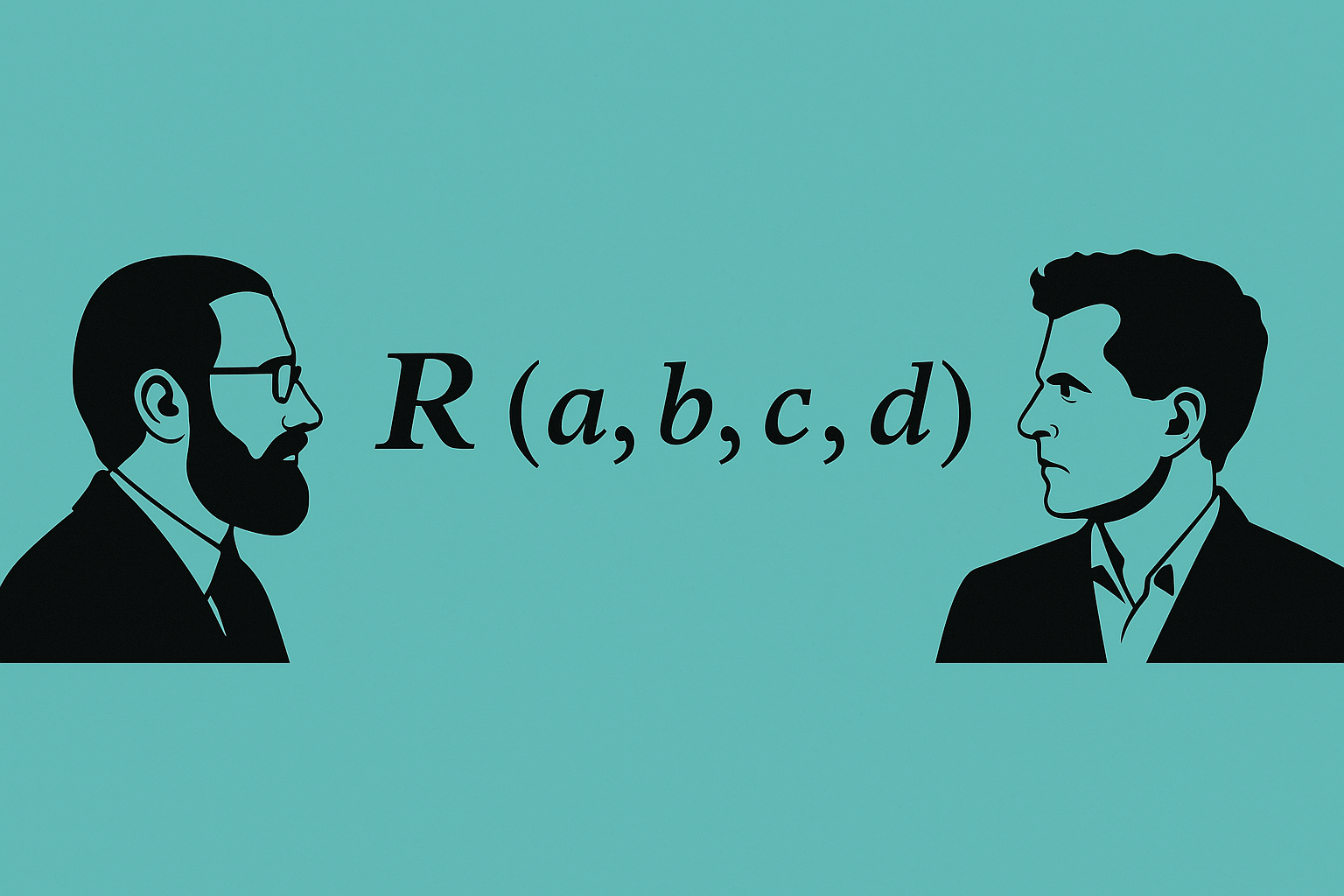

And if we listen closely, we can hear echoes of another great mind: Ludwig Wittgenstein. From opposite ends of the intellectual spectrum, Dijkstra and Wittgenstein converged on a single, urgent theme: language shapes — and often distorts — how we think.

The Problem with Natural Language Dijkstra believed that programming is not just writing instructions for a computer; it’s writing instructions that must be perfectly unambiguous. Natural languages like English are ill-equipped for this. They’re too loose, too riddled with assumptions. A computer doesn’t “guess” what you mean — it does exactly what you say.

“The purpose of a programming language is to communicate a program and nothing else: it should be designed so as to be easily and mechanically translatable into efficient machine code.”

This demand for precision is not an arbitrary fetish — it’s a survival strategy in the world of software, where ambiguity leads to failure.

Wittgenstein and the Limits of Language Dijkstra’s frustrations parallel the two Wittgensteins: the early and the late. In the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, early Wittgenstein insists that language must mirror reality, and only statements with a clear logical form have meaning. This aligns neatly with Dijkstra’s formalist mindset.

But later, in Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein turns the tables. Language, he argues, is not a mirror but a set of practices — “language games” we play in context. Meaning is use. And while this insight illuminates the richness of human communication, it also reveals its unreliability. Words mean different things to different people. Grammar is a guideline, not a law. Precision is the exception, not the rule.

Dijkstra saw this fuzziness not as beauty, but as danger.

Example where Natural Language Fails: The Missing Predicate Problem A striking example of natural language’s limitation is its clumsy handling of multi-entity relationships. Binary predicates? Fine. Ternary? Awkward but doable. But four-place predicates? Natural language begins to break down.

R(a, b, c, d)Transaction(User1, User2, Amount, Timestamp)

Natural language, in contrast, collapses into ambiguity:

“She transferred money to him last Thursday during the conference.”

Was the timestamp about the transfer or the conference? Who exactly was involved? What counts as the event? The sentence hides more than it reveals.

This is where formal languages show their strength — not as replacements for human expression, but as tools for clarity in complexity.

The Void of Stupidity: From Formalism to Cultural Critique

Dijkstra’s critique of natural language was part of a broader fear: that rigorous analysis is being replaced by rhetorical noise. He feared a society drifting away from logic, drowning in unexamined assumptions and emotional appeals.

Fast-forward to today, and his fears feel prophetic. Public discourse has devolved into linguistic theatre. The tools of analysis are dismissed as elitist or inconvenient. Ironically, the linguistic scepticism once used by the academic left to critique power structures is now used by the populist right to undermine truth altogether.

Much of the liberal-left intellectual tradition more and more prided itself on moral sensitivity and emotional nuance — but often at the expense of analytical precision. In prioritizing feeling over form, affect over clarity, it ironically paved the way for the rise of a reactionary right that did not only hate the content of the elitist left’s ideas but learned to weaponize these same linguistic tools, only to go further: by rejecting or at least ignoring not just emotionless logic, but the very idea of objectivity, of science, of truth itself.

This is the double irony of our moment:

- The left, in its rhetorical looseness, hollowed out the authority of precision.

- The right, seizing that vacuum, has declared war on rigor altogether. And happens to find old weapons newly sharpened by decades of unrigorous academic rhetorical theatre.

And now, at exactly this historical juncture, machines have begun to simulate understanding of natural language. Tools like large language models generate plausible-sounding prose with astounding fluency — but without grounding, without true comprehension, without the rigor that Dijkstra would have demanded. In doing so, they add another layer to the fog: producing yet more words, more surface coherence, more illusions of meaning.

We risk sinking deeper into the swamp — not because machines are stupid, but because they reflect our own abandonment of disciplined thought. The machines speak our language all too well. And that may be the most dangerous thing of all.

We speak about AI as if it thinks. But the real crisis is that we’ve stopped doing so. We outsource not only computation, but cognition. In a world where every question is met with a generated answer, the art of asking precise, rigorous questions — the true essence of thought — may become lost.

Worse still, we may have unlearned the very critical thinking required to detect where these machines go wrong. Having trained them on imprecise, emotionally loaded, and analytically weak data, we risk creating systems that mimic our worst habits — and lack the very structure of thought necessary for meaningful correction. We taught them to speak in a haze, and now we struggle to see through it ourselves.

Dijkstra might say: “You have taken the slippery nature of language as an excuse to abandon rigor — and now, all discourse is quicksand.”

Wittgenstein never intended his language games to justify chaos. But in the wrong hands, his insights have become cover for a dangerous relativism.

Precision as Resistance In a world where ambiguity is a political tactic and meaning is manipulated for effect, the demand for precision becomes a form of resistance. Symbolic languages — math, code, logic — are not merely technical tools. They are disciplines of the mind. They force us to say exactly what we mean, or say nothing at all.

Wittgenstein warned us of language’s limits. Dijkstra showed us the cost of ignoring them.

If we want to think clearly — and build systems, societies, and arguments that endure — we must return to precision. Because in the end, the enemy isn’t just bad code or bad grammar.

It’s bad thinking.

Speculative Future: Echoes in the Fog As we move forward, we must consider the world we are constructing — not just technologically, but epistemologically. If we continue to train machines on the detritus of our imprecise discourse, we may enter an era where machines appear articulate, but no one understands anything. Conversations will be simulations of coherence, not vessels of understanding.

In such a future, what looks like intelligence may be little more than recursion in a hall of mirrors. The danger is not that machines will think like us — but that we will forget how to think differently. That we will come to accept approximation as adequacy, and persuasion as proof.

The fight for rigor, then, is not just academic. It is existential. Precision may well become the only remaining sign of intentional thought — the last light we can trust in a fog of synthetic fluency.

Closing Thought As Wittgenstein said: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

Dijkstra, ever the pragmatist, might have added: “Or better yet, write a compiler.”

But perhaps today we must go further:

The compiler won’t save us. Not if we don’t know how to write the spec.