The Unsung Marvel: How AI Bridges Babel – And Why Translation Remains a Philosophical Enigma

Introduction: The Quiet Revolution of NLM Translation

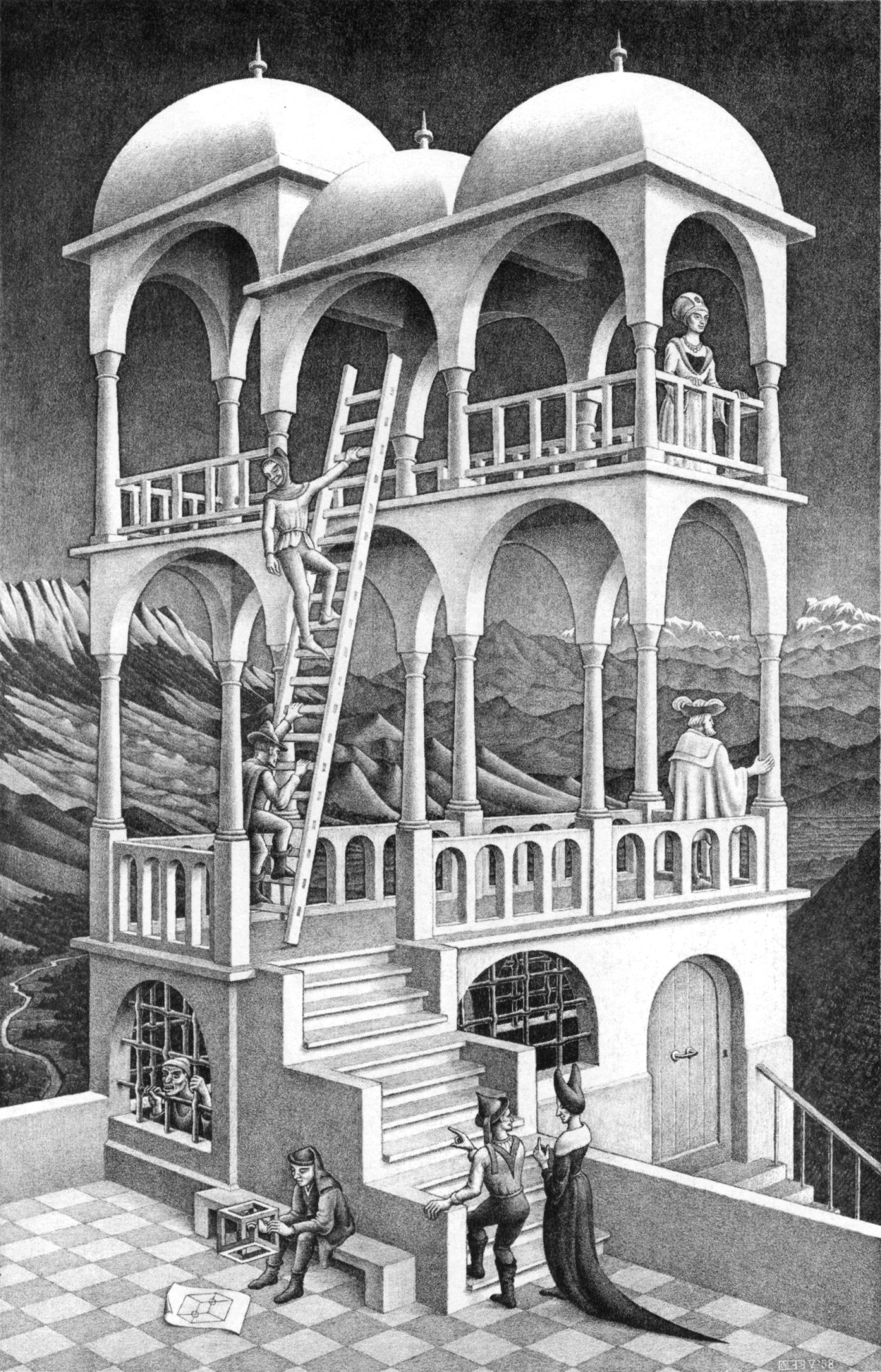

The biblical narrative of the Tower of Babel [1, 2] stands as a potent metaphor for humanity’s enduring struggle with linguistic diversity and misunderstanding. For millennia, the dream of universal comprehension remained elusive, a testament to the “confusion of tongues”.[2] This ancient story underscores a fundamental human need: to overcome the barriers that separate us through language.

In recent years, Natural Language Models (NLMs), particularly those leveraging Neural Machine Translation (NMT) and Large Language Models (LLMs), have achieved a remarkable feat: they have significantly bridged these linguistic divides.[3, 4, 5] This profound achievement, often overshadowed by louder public concerns surrounding AI, such as its substantial energy consumption, the potential for widespread job displacement, and broader ethical implications [6, 7], represents perhaps the most significant technical and practical solution to one of humanity’s oldest communication challenges. By effectively removing the functional speech barrier, NLMs allow us to communicate across languages with unprecedented ease. The public is rightly concerned about AI’s societal impact, with job security worries significantly increasing after exposure to AI’s creative capabilities.[7] This “din” can inadvertently obscure a truly transformative capability that impacts daily life and global connectivity.

The question that arises is whether we have truly “solved” the Babel problem in an absolute sense. Or, as philosophers like Jacques Derrida and Ludwig Wittgenstein, among others, suggest, does the very nature of language and meaning inherently limit the possibility of perfect translation, regardless of technological prowess? This post will explore this tension between technological triumph and philosophical enigma, arguing that while AI offers unprecedented practical solutions, allowing us to focus on the true Babylonian issue—the deeper, philosophical questions of meaning and untranslatability—these deeper questions persist.

A fascinating paradox unfolds when considering the claim that NLMs have “quasi-solved” the Babylonian confusion of tongues. The biblical narrative describes God intentionally “confounding” (“balal,” to confuse or mix up) human language to thwart their unified, presumptuous plans – the building of a tower to heaven.[1, 2] The “confusion” was a divine act of dispersion, a punishment for human hubris. NLMs, by facilitating communication across linguistic divides, counteract this divine dispersion, enabling a new form of human unity through understanding. This implies that the “solution” is not a return to a single Adamic language, which historical linguistics regards as pseudolinguistics.[1] Instead, it is a technological means of interoperability among inherently diverse languages. The conclusion is that AI does not restore a mythical linguistic homogeneity but rather creates a technologically mediated global multilingualism. This shifts the focus from eliminating linguistic diversity to managing it with unprecedented efficiency, creating a “smarter Babel” rather than a pre-Babel state. This has profound implications for global cooperation, cultural exchange, and the fabric of international relations, suggesting a future where language barriers are less about inherent divisions and more about technological access.

From Myth to Machine: The Modern Babel Solution

![]()

The narrative of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11:1-9 describes a time when “the whole earth was of one language and of one speech”.[2] Humanity, in its hubris, attempted to build a city and a tower “whose top may reach unto heaven” to “make us a name” and prevent dispersion.[2, 8] Yahweh, observing their unified power, “confounded their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech, and scattered them abroad upon the face of all the earth”.[1, 2] The city was named “Babel” from the Hebrew “balal,” meaning “to confuse”.[1, 2] This myth serves as a foundational narrative for linguistic diversity and the inherent challenge of cross-cultural communication.

For centuries, overcoming these language barriers required immense human effort, relying on skilled polyglots, interpreters, and painstaking manual translation. The “confusion of tongues” was a practical, everyday reality that limited global interaction and understanding, hindering everything from trade to diplomacy to scientific collaboration.

Modern advancements in artificial intelligence, particularly in Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Natural Language Understanding (NLU) [9], have ushered in a new era of machine translation, effectively providing a technical and practical solution to the age-old problem of linguistic barriers. Neural Machine Translation (NMT), powered by deep learning techniques and transformer-based architectures, has revolutionized the field [3, 4, 5], making high-quality, real-time translation a widespread reality and removing the functional speech barrier for countless interactions.

Key advancements include foundational technologies driving NMT, such as deep learning and neural networks, attention mechanisms, and transformer infrastructures, which have significantly improved translation precision.[5] The integration of advanced Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT promises a substantial boost in quality, enabling more natural-sounding outputs and better contextual understanding.[3, 10] These adaptive MT models continuously process and learn, ensuring translations remain accurate and current with linguistic trends.[4]

A fundamental paradigm shift in machine translation is evident. Early machine translation often relied on rule-based systems or statistical word-for-word mappings, leading to literal and often awkward translations. Current developments, characterized by transformer architectures, attention mechanisms, and deep learning techniques [3, 4, 5], enable models to “excel at understanding linguistic nuances, context, idiomatic expressions, and domain-specific terminology”.[4] It is explicitly stated that LLMs “grasp the broader context of text, enabling more natural-sounding outputs”.[10] This means modern NLMs are not merely mapping individual words or phrases between languages but are attempting to model meaning and intent within a broader textual and even conversational context. This allows them to handle complex linguistic phenomena like idioms and subtle nuances far more effectively than previous generations of machine translation. The shift from static models to adaptive, self-learning algorithms [4] further enhances this contextual awareness and real-time adaptation, allowing translations to keep pace with evolving language use. This evolution signifies that NLMs are not just linguistic tools but are increasingly capable of mediating meaning across language boundaries, making global communication more fluid and less prone to simple misinterpretations. This indicates that AI is moving beyond mere language conversion to a form of interlingual interpretation, albeit one based on statistical patterns rather than human lived experience.

NLMs in Action: Capabilities and Current Realities

Modern NLMs demonstrate impressive capabilities across various content types, from product documentation and marketing materials to legal and life sciences documents where specialized terminology is crucial [3, 4], showcasing the technical and practical solution they offer for diverse communication needs. They are increasingly integrated into real-time communication platforms like chatbots, video conferencing tools, and customer support systems, enabling instantaneous multilingual conversations and expanding global reach for businesses.[3, 4] Multimodal Machine Translation (MMT) further extends this by integrating text, audio, and visual elements for richer translation, particularly valuable in media, gaming, and entertainment industries.[3, 4]

Recent studies and evaluations confirm that LLM-based solutions outperform traditional machine translation systems.[10] They show superior performance across various language pairs, with top models like Claude Sonnet 3.5 delivering “good” translations approximately 78% of the time, even without explicit context.[10] LLMs are praised for their fluency, natural-sounding outputs, ability to handle longer contexts, adapt tone, and rephrase content.[11] For conversational or informal content, LLMs like GPT-4 can perform on par with human junior translators in terms of overall error count, especially for general-domain text.[11]

The Philosophical Aporia: Derrida on the “Necessary Impossibility” of Translation

Jacques Derrida, a key figure in deconstruction, radically problematizes translation.[12, 13] For Derrida, philosophy traditionally prioritizes “thought” or “concepts” over “writing” or “linguistic inscription,” viewing writing as secondary, marginal, and potentially dangerous.[12] Deconstruction challenges this “logocentrism”—the deep-seated desire for an absolute truth or objective meaning that transcends language itself.[13]

Derrida argues that translation is not merely an external process but a fundamental condition of philosophy itself, as philosophy cannot escape its own linguistic inscriptions.[12] He famously asserts that “there is nothing outside of the text” [13], meaning that meaning is always constructed within language and its interpretations, never existing as a pure, pre-linguistic concept.

For Derrida, translation is simultaneously “necessary and impossible”.[8, 12] It is necessary because for an “original text” to survive and continue to be read, it requires translation, whether into other languages or through the unique, irreducible act of reading itself.[12] Yet, it is impossible in the sense that a “pure transition” without “loss of signification” is unattainable.[14] The act of translation inherently disrupts the opposition between “original” and “translation,” making translations themselves “originals awaiting their translation”.[12] This implies that the “original” is never truly fixed or complete.

Derrida uses the proper name “Babel” as a prime example of this paradox.[8, 12] “Babel” is an untranslatable proper name that resists all attempts at exact correspondence, as its meaning is tied to its unique historical and mytical context, yet its biblical story [1, 2] necessitates translation to convey its significance and the confusion it represents. The name itself is ambiguous: is it a proper name or a common noun meaning “confusion”?.[8] This inherent undecidability makes translation a “debt and a duty” that can never be fully discharged, a relentless pursuit of the impossible.[8, 13]

Deconstruction reveals that meaning is inscribed with “différance,” a concept embodying both difference and deferral.[13] This means meaning is never fully present or complete; it is always in flux, defined by its relation to other signs, by what is included and excluded, and constantly open to reinterpretation. Translation, therefore, aims at an impossible ideal of “balanced and complete books or finished transferable meanings”.[12]

While popular discussion and the initial query tend to view the “Babylonian confusion” as a problem that can be definitively “solved” in an absolute sense, Derrida’s philosophy, serving as an exemplary witness to this broader philosophical challenge, as articulated in sources [8, 12, 13], fundamentally challenges the notion of perfect translation. However, this philosophical perspective does not diminish the technical and practical solution that NLMs have provided for everyday communication. Indeed, by removing the functional speech barrier, NLMs allow us to confront the true “Babylonian issue”: the inherent, philosophical untranslatability that remains. He argues that the “impossibility” of translation is not a technical failure that could be overcome by better algorithms, but an inherent, structural property of language itself—an “aporia” that constitutes a “condition of philosophy.” The untranslatability of proper names like “Babel” [8, 12] is not a deficiency in linguistic tools but a profound demonstration of language’s inherent ambiguity and its resistance to fixed, singular meaning. If meaning is always deferred, relational, and differential (“différance” – [13]), then a perfect, one-to-one mapping between languages that preserves all “significations” [14] is logically impossible. This suggests that “loss of signification” [14] in translation is not a bug to be eliminated by more sophisticated algorithms but an unavoidable aspect of how language functions. While NLMs can achieve impressive functional equivalence and high fluency for practical purposes [10, 11], they cannot overcome this fundamental philosophical hurdle of absolute fidelity or capturing a “pure” meaning that does not exist. This reframes how we view the “problem” of translation. Rather than striving for an unattainable ideal of perfect equivalence, one should acknowledge translation as an ongoing process of reinterpretation, negotiation, and creative transposition. AI’s role, then, is not to achieve an impossible perfection but to enable highly effective approximations that facilitate practical communication, while the philosophical questions of ultimate meaning and untranslatability persist. The “Babylonian confusion” is thus not “solved” in a definitive sense but managed and navigated with unprecedented efficiency, highlighting the enduring mystery of language itself.

Language as Game: Wittgenstein’s Perspective on Meaning and Limits

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s later philosophy, particularly in Philosophical Investigations, rejects the notion that language is separate from reality or that words have meaning independent of their use.[15, 16] Instead, he introduces the concept of “language-games,” which are “forms of language simpler than the totality of a language itself, ‘consisting of language and the actions into which it is woven’”.[15, 17] Meaning, for Wittgenstein, derives from the “rule” of the “game” being played, and “the speaking of language is part of an activity, or a form of life”.[15, 16] This means understanding a word, is akin to knowing how to play a particular game with it.

The meaning of a word is its use within a specific language-game. For instance, “Water!” can be an exclamation, an order, a request, or a warning, depending on the context and the “game” being played.[15] This also applies to sentences; a sentence is “meaningless” if it is not used for a specific purpose.[15] Natural language is seen as a “family of language-games,” with meanings blending into one another through “family resemblance”.[15]

Although Wittgenstein did not develop a formal theory of translation, his ideas significantly inform it.[16] The goal of translation, from this perspective, is not to reproduce the exact unity of content and form or to achieve an equivalent effect, but rather to “play the same language-game” in the target language.[16] This functionalist approach grants translators the freedom to render the “untranslatable” into the translatable by focusing on the function or use of the original text rather than a literal mapping.[16] One work [16] outlines a three-step procedure: identify the language-game in the source text, describe its use, and then play the same language-game in the target language under using appropriate linguistic or non-linguistic means.

This framework illuminates why cultural nuances, idiomatic expression, humor, and tonal variations pose significant challenges for translation.[18, 19] A simple word-for-word translation fails to capture these elements because they are deeply embedded in specific “forms of life” and “language-games”.[18] For example, an idiom like “It’s raining cats and dogs” must be adapted to a culturally relevant equivalent (“Il pleut des cordes” in French) to play the same “game” of describing heavy rain, rather than a literal, nonsensical translation.[18] Similarly, formality, humor, and even color symbolism vary drastically across cultures, requiring deep cultural understanding to ensure the translated content resonates appropriately.[18]

Wittgenstein’s central concept that language is “woven into actions” and part of a “form of life” [15, 16] implies that meaning is not purely abstract but deeply embedded in human experience, social practices, and shared understanding. Further evidence [20, 21] supports this by showing how human communication emerges early, is profoundly social, and involves integrating myriad linguistic and pragmatic cues, with bilingualism even enhancing cognitive control and meta-linguistic insight. This suggests a profound, embodied connection between language and lived experience. NLMs can, although they process vast amounts of text and identify statistical patterns [10], not participate in a “form of life” in the human sense. They do not experience emotions, engage in social rituals, possess cultural sensitivities, or develop through childhood.[18, 19, 20] Therefore, while they can mimic the outcome of a language-game by predicting the most probable word sequence, they cannot truly play it in the human, embodied sense. This explains why they struggle with humor, subtle social cues, and deeply embedded cultural nuances [11, 18], where “meaning” extends beyond mere linguistic form. The “loss of signification” [14] in these areas is not just about missing words but missing the lived context and shared experience that give those words their full meaning. This suggests that while NLMs can provide highly functional and fluent translations for many purposes, especially for factual or general content [11], they will always encounter an inherent limit in translating the full richness of human experience and cultural expression. The “Babylonian confusion” has been technologically bridged for practical communication to an unprecedented degree, effectively removing the functional speech barrier, but the unique “forms of life” underlying each language remain distinct, making absolute equivalence a philosophical, not just technical, impossibility. The “solution” is thus partial, addressing the practical communication gap while leaving the deeper, existential aspects of linguistic diversity intact.

Beyond the Algorithm: What NLMs Still Can’t “Solve”

Despite their impressive advancements, NLMs continue to face significant limitations, particularly when confronted with the complexities highlighted by philosophical theories of translation and the nuances of human communication. Studies show that even in specific, highly sensitive domains like medical translation, machine tools make errors that a human translator avoids, such as using outdated terminology, incorrect medical terms (e.g., “cricothyrotomy” translated incorrectly), or misinterpreting common phrases like “patient-centered care”.[3] These are not minor errors but can have significant real-world consequences.

The core challenge lies in cultural nuances, which encompass subtle differences in customs, traditions, social behaviors, tone, and humor.[18, 19] NLMs struggle with:

- Idiomatic Expressions and Slang: Direct translation often leads to loss of meaning.[18]

- Formality and Tone Variations: Different languages have varying degrees of formality, which AI can misinterpret, leading to inappropriate or disrespectful communication.[18]

- Humor and Wordplay: What is funny in one language often does not translate well due to cultural sensitivities or untranslatable wordplay, leading to literal and less diverse outputs.[11, 18]

This philosophical understanding underscores that if even something as seemingly universal as color is subjectively experienced and culturally imbued with meaning, then the complexities of human language—with its idioms, humor, and social cues—are even more resistant to purely algorithmic translation. NLMs, operating on statistical patterns, struggle to fully grasp these deeply ingrained cultural and emotional associations, leading to potential misinterpretations or offensive content if not handled by human expertise.[18, 19]

Performance across certain content types and languages also varies. While LLMs excel at conversational or informal content [11], their accuracy significantly drops for technical, domain-specific, creative, or literary texts, where error rates are higher compared to human subject matter experts.[11] They also struggle with “low-resource languages” due to less available training data, leading to frequent semantic errors.[11] Common errors include overly literal translations, wrong word choice due to ambiguity, tone mismatch, and even “hallucinations” or made-up content.[11]

The persistent “loss of signification” remains a reality, as discussed by philosophers like Steiner and Cassin.[14] Translation, especially of poetry or philosophical texts, often involves a “loss of signification.” While some argue that “all cognitive experience… is conveyable in any existing language” (Jakobson [14]), the nuances, poetic value, and deep contextual meanings can be diminished. This “conditional untranslatability” [14] means that while a text can always be translated in some form, it cannot be done without significant transformation or reinterpretation, implying that some “loss” or “change” of meaning is inherent.

These limitations, while real, primarily highlight the need for human oversight in highly nuanced or critical contexts, rather than negating the broad practical solution NLMs offer. Human translators and localization experts possess the deep cultural understanding, intuition, and nuanced judgment that AI currently lacks [18], making them essential for refinement and cultural appropriateness. The rise of “Post-Editing Machine Translation (PEMT)” [3, 4] signals a hybrid approach where human expertise reviews and refines machine output, combining the efficiency of machines with the accuracy and cultural sensitivity of human insight. This synergy is projected to grow significantly, with the machine translation market expected to triple by 2027.[4]

While NLMs achieve impressive fluency and contextual understanding [10, 11], the detailed errors identified in medical translation [3] and the struggles with cultural nuances, humor, and creative texts [11, 18] reveal a qualitative gap that goes beyond mere statistical accuracy. The nature of these errors—misinterpreting “patient-centered care,” using outdated terms, or failing to adapt humor—suggests a lack of true understanding of human values, social norms, emotional resonance, and the lived experience that imbues language with its deepest meaning. This points to an “uncanny valley” effect in translation: AI can come very close to human performance, but its failures in areas requiring deep cultural and emotional intelligence are jarring and highlight its fundamental difference from human cognition. This is where the “human advantage” [20, 21] comes into play. Human translators, with their embodied experience and participation in “forms of life,” can navigate these subtleties, make creative leaps, and ensure cultural appropriateness. The need for “post-editing” [3, 4] and “localization experts” [18] demonstrates that the “solution” for Babel is not purely algorithmic but a synergistic human-AI partnership, where human oversight is crucial for highly sensitive or deeply nuanced content. The continued reliance on human oversight for critical or culturally sensitive translations implies that while AI has democratized basic cross-lingual communication, effectively removing the functional speech barrier, the highest realms of translation—those requiring true empathy, cultural sensitivity, and creative re-expression—remain firmly in human hands. The “Babylonian confusion” is thus not eliminated by AI but transformed into a new collaborative challenge, where machines handle the bulk of routine translation, and humans refine the soul and ensure the cultural resonance of the message.

📦 Color as Cultural Code: A Philosophical Sidebar (which I have to do)

![]()

“If even something as seemingly universal as color is subjectively experienced and culturally imbued with meaning, then the complexities of human language […] are even more resistant to purely algorithmic translation.”

Color, much like language, is not just a physical phenomenon but a deeply embedded cultural and psychological construct. Philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe have long challenged the view of color as a purely objective reality.

-

Rather, Schopenhauer emphasized that vision is “wholly subjective in nature” and that colors have an affective power—they influence our emotional state. For him, perception itself is an act of the subject, not a passive recording of external stimuli.

-

Goethe, in his Theory of Colours, argued that color emerges from the dynamic interplay between light and darkness, not from objective wavelength measurement. He observed how different colors evoke distinct emotional reactions:

- Yellow appears “serene and cheerful,” but when sullied, it takes on a tone of ignominy.

- Blue suggests “coldness” and “recession,” producing a feeling of withdrawal or contemplation.

These insights suggest that color is not only a perceptual experience but also a cultural symbol—imbued with meanings that vary by time, place, and tradition. Translating color symbolism across languages and cultures—such as white symbolizing purity in the West but mourning in parts of Asia—requires deep cultural knowledge and empathy.

Hence, just as color escapes universal categorization, so too does language resist one-to-one translation. Both are shaped by experience, context, and culture, and both reveal the profound limitations of any system—AI included—that attempts to reduce meaning to mere code.

![]()

A curious footnote: despite certain philosophical affinities regarding the nature of perception, the relationship between Schopenhauer and Goethe ended in disillusionment. Goethe considered Schopenhauer’s proposals not a continuation, but a contradiction of his own theory. Schopenhauer—whose mother frequently hosted Goethe in her literary salons, and who had conducted experiments in Goethe’s colour laboratory—was ultimately distanced by the elder polymath. Goethe saw the younger man’s elaborations as a betrayal of his phenomenological approach. Even in those matters of colour, the spectrum of interpretation proved divisive.

Conclusion: A Smarter Babel, But Still Babel?

Natural Language Models have indeed achieved a technological marvel, providing a profound technical and practical solution to the age-old problem of linguistic barriers. They have significantly reduced practical communication challenges and enabled an unprecedented level of cross-cultural interaction [3, 4], effectively removing the functional speech barrier that has long hindered global understanding. This quiet revolution, often overshadowed by broader AI concerns [6, 7], represents a deep step forward for global connectivity, changing how individuals and organizations interact across linguistic divides.

However, the journey into NLMs’ capabilities also illuminates the persistent philosophical complexities of translation, as articulated by philosophers like Derrida and Wittgenstein, who stand as prominent examples of this ongoing inquiry. Derrida’s concept of translation as “necessary and impossible” [8, 12] serves as a reminder that perfect equivalence is an elusive ideal, and meaning is inherently fluid, contextual, and perpetually deferred. Wittgenstein’s “language-games” [15, 16] underscore that meaning is deeply interwoven with human activity, culture, and “forms of life” [15]—aspects that even the most advanced algorithms struggle to fully grasp and replicate.[11, 18]

While NLMs have made communication across languages vastly more efficient and accessible, they have not, and perhaps cannot, resolve the fundamental ambiguities and cultural embeddedness that define human language. The “loss of signification” [14] remains a reality, particularly in areas requiring deep cultural nuance, creativity, or philosophical depth. The “solution” to Babel, therefore, is not a return to a single, unified language but a sophisticated technological bridge that allows us to navigate the inherent diversity of human expression, making the world smaller without making it homogeneous. This practical bridging of the communication gap allows us to focus on the true Babylonian issue: the deeper, philosophical questions of meaning, untranslatability, and the inherent nature of language itself.

As AI continues to evolve, it is crucial to maintain a nuanced understanding of its capabilities and limitations. We must celebrate the practical triumphs of NLM translation while remaining critically engaged with the deeper philosophical questions of language, meaning, and the nature of human understanding. The Tower of Babel may be technologically bridged, but the profound mystery of linguistic diversity and the art of true cross-cultural comprehension continue to unfold, demanding a collaborative future where human insight complements algorithmic power.

- [1] https://www.biblicaltraining.org/library/confusion-of-tongues

- [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tower_of_Babel

- [3] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12239318/

- [4] https://vistatec.com/the-current-state-of-machine-translation-and-future-predictions/

- [5] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384862426_Innovations_and_Challenges_in_Neural_Machine_Translation_A_Review

- [6] https://jacobin.com/2025/07/artificial-intelligence-regulation-public-utility

- [7] https://theaipi.org/poll-biden-ai-executive-order-10-30-7-2-4-2-2-2/

- [8] http://mural.uv.es/elgagar/babel.html

- [9] https://www.amazon.science/publications/adapting-long-context-nlm-for-asr-rescoring-in-conversational-agents

- [10] https://lokalise.com/blog/what-is-the-best-llm-for-translation/

- [11] https://lokalise.com/blog/can-llm-translate-text-accurately/

- [12] https://that-which.com/derrida-on-translation-necessary-and-impossible/

- [13] https://criticallegalthinking.com/2016/05/27/jacques-derrida-deconstruction/

- [14] https://journals.openedition.org/edl/3898?lang=en

- [15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language_game_(philosophy

- [16] https://tpls.academypublication.com/index.php/tpls/article/download/7873/6377/23816

- [17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language_game_(philosophy)#:~:text=Wittgenstein%20used%20the%20term%20%22language,by%20family%20resemblance%20(Familien%C3%A4hnlichkeit.

- [18] https://ad-astrainc.com/blog/the-impact-of-cultural-nuances-on-translation-accuracy

- [19] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21671700/

- [20] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2774929/

- [21] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5031504/

- [22] https://www.boijmans.nl/en/collection/in-depth/bruegel-s-tower-of-babel

- [23] https://www.themarginalian.org/2012/08/17/goethe-theory-of-colors/

- [24] http://ducts.sundresspublications.com/content/art-gallery/art-bridges-gaps-and-creates-a-common-language/

- [25] https://ttgtranslates.com/artwork-as-a-powerful-form-of-artful-communication/

- [26] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/conceptual-art

- [27] https://www.britannica.com/art/conceptual-art

- [28] https://www.swaggermagazine.com/culture/10-artists-combining-image-and-text-that-you-should-know/

- [29] https://www.shutterstock.com/search/communication-breakdown?image_type=illustration

- [30] https://www.shutterstock.com/search/communication-breakdown

- [31] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/7155000-on-vision-and-colors-by-arthur-schopenhauer-color-sphere-by-philipp-otto

- [32] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/19375922-on-vision-and-colors

- [33] https://www.themarginalian.org/2012/08/17/goethe-theory-of-colors/

- [34] https://uxplanet.org/the-absolutely-mind-warping-simplicity-of-goethes-theory-of-colors-47e633b459cc

- [35] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fD7OY4b4LoE

- [36] https://uxplanet.org/the-absolutely-mind-warping-simplicity-of-goethes-theory-of-colors-47e633b459cc

- [37] https://savantsandsages.com/2023/09/17/goethes-theory-of-colors/

- [38] https://books.google.com/books/about/On_Vision_and_Colors.html?id=pmnOR8Br2sEC&hl=en

- [39] https://savantsandsages.com/2023/09/17/goethes-colour-theory#:~:text=Goethe%20proposes%20the%20existence%20of,arrangement%20on%20a%20colour%20wheel.